Good morning. Welcome to the Saturday Read. For any first-time readers this is the New Statesman’s weekly guide to the best writing on politics, culture, books, and ideas, sent to NS subscribers and registered readers. This is Harry, along with Will, Pippa, and George Monaghan. Don’t miss Anna Leszkiewicz’s cultural reflection below, written for today’s email, or Will’s sign-off on Evgeny Lebedev’s new… podcast.

Alexei Navalny is dead, eleven years after the assassination of Boris Nemtsov, the one other Russian opposition leader who threatened Putin. “Don’t do nothing. If they decide to kill me it means that we are incredibly strong,” Navalny implored in the final moments of a documentary I haven’t forgotten watching. At one point he calls up the men who tried to kill him and deceives one of them into divulging what went wrong. Why did he go back to Russia? It’s a question you will ask as you watch him doing it. For more on the man, who wanted to be Russia’s Mandela, try this piece of ours.

Donald Trump was found guilty of fraud and fined $350 million, plus interest, by a New York judge who used to ride a cab. In January, Trump was ordered to pay $83 million in damages to E. Jean Carroll after defaming her, having been found guilty of sexually abusing her in 2023. It was another notable week for America’s most probable president in 2025.

Click to read online if this email cuts off. If you already subscribe to the NS, thank you. If you don’t yet and these pieces intrigue, perhaps you’d like to try a subscription. If you enjoy the Saturday Read we’d welcome any readers you think may enjoy it too.

1—“This is the American wreckage neoliberals of both parties left behind.”

Sohrab Amari interviews JD Vance, the turncoat Republican senator for Ohio and possible Trump VP pick. Vance wondered in 2016 if Trump was “America’s Hitler” when he broke onto the political scene with Hillbilly Elegy, his Appalachian lament. Then he decided to run for Senate and begged Trump for support.

Some readers on Twitter objected to us “platforming” Vance, but isn’t it always more interesting to hear from the people you disagree with? The NS sent HG Wells to interview Stalin in 1934. You take the interview. Sohrab thinks Trump’s attempt to subvert American democracy in 2020 secondary to the promise of his policy agenda. I don’t. See what you think. HL

Who belongs? “This is obviously a very Catholic insight [but] I’m totally OK saying, ‘Yes, we have some obligation to the world at large, but we owe a more pressing obligation to people in our community.’ I think the left is uncomfortable with accepting that people feel bonds of kinship with the people that they live amongst, that’s much stronger, that is in fact the raw materials for how to build a truly social democracy. And if you erode that… you defeat the left’s own social aspirations.”

2—“Catastrophe awaits.”

Bruno Maçães describes the situation in Gaza. Palestinians have been told to relocate further and further southwards. Now 1.5 million people have reached Rafah – and the concrete wall on the Egyptian border. Netanyahu plans to invade. There is no credible plan for evacuation. GM

Under normal circumstances, the mere threat of Cairo sending its tanks to meet the Israeli troops north of Rafah would have alarmed Washington, and the bluff would have at least forced Israel to reconsider a ground offensive. These are not normal circumstances.

The way the Biden administration has extended full support to the Netanyahu government has been profoundly destabilising because it allows Israel to act seemingly with complete abandon, certain that the US would intervene only to stop, say, a Hezbollah attack in the north, or a confrontation with Egypt, or a spiralling conflict in the wider region involving Iran. It is difficult to imagine that Israel could act with such indifference to the consequences of its own actions if it did not have the best insurance policy in the world.

3—“Toppling a leader is like pushing over a fridge.”

All is not well in Toryland. As the party faces collapse, its various factions are fighting two fierce battles: over who will succeed Rishi Sunak and over which narrative of Tory failure will win out after defeat. Rachel Cunliffe offers the inside story on the Tory blame game in this week’s cover. Kemi Badenoch and others are, like David Miliband in 2009, waiting for Sunak to fail rather than challenging him now. PB

The battle for the Red Wall, one Tory insider told me, is already lost. A YouGov poll, published on 30 January, found that only 29 per cent of people who were Labour-Tory switchers in 2019 planned to back the Conservatives at the next election. Reducing immigration remains a priority for 2019 Conservative voters in Red Wall seats, but they no longer believe the government can achieve it. The focus, the insider said, had to be on fending off the Lib Dems to minimise losses in the traditional southern heartlands. But that is of little consolation to those facing the loss of their jobs, in part, because of the rise of Reform.

4—“Don’t you realise what this means? Britain is no longer an island.”

Parallels abound between the Edwardian era and our own, Andrew Marr writes in this arresting review of a new book by Alwyn Turner. “Turner’s specialty, as in his books about modern Britain, is using popular culture as the lens through which to squint at everything else.” HL

The parallels are also more subtle. Think of a right-wing observer such as the short-story writer “Saki” (HH Munro) warning against the liberal intelligentsia who use “the jargon of denationalised culture”, or the Edwardian scares about migration. If we have the Rwanda Bill, they had the 1904 Aliens Bill to exclude undesirable immigrants. Around 100,000 Jews arrived by steamer – rather than small boats – during the period, mostly escaping Russian pogroms after the assassination of Tzar Alexander in 1881.

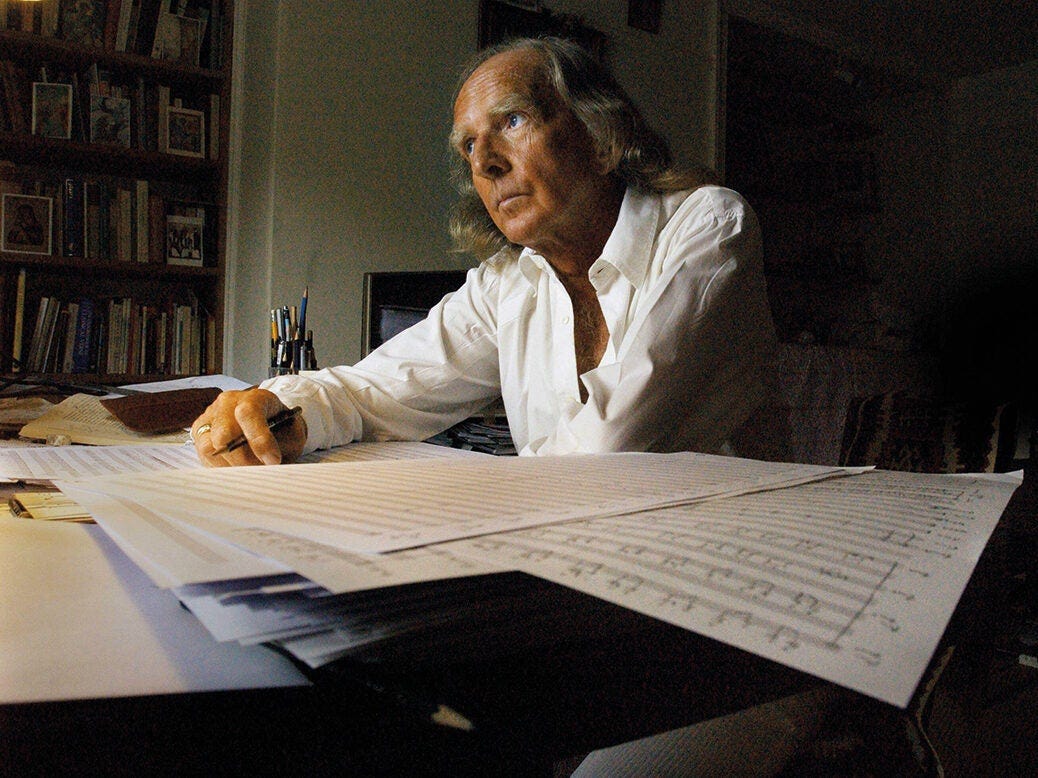

5—“The cellist is playing in the stratosphere for much of the time.”

“Why does the secular mind seek out the sacred, often at moments of heightened stress or torment?” Asks Jason Cowley, our editor, in this reflection on John Tavener, whose music will transport you to another realm. “What is it we feel we are missing or, more accurately, seeking? What is this absence for which we yearn but of which we cannot speak?”

More and more, in recent times, I find myself listening to sacred music, not because I am religious but because it unlocks something deep within – a longing for transcendence, perhaps, or what Philip Larkin, in “Church Going”, calls a hunger in oneself to be more serious. After he had a stroke, my colleague Andrew Marr, who is not a believer, found consolation through listening to Bach’s cantatas and reading religious poetry. Confronted by the “possibility of sudden death”, he had sought solace in religious art or art inspired by religion.

Thank you to the 4,546 readers who answered last week’s poll. Let us know what you think of today’s in the comments. What’s missing – AI? Jihadism? TikTok? The undue glare of LED light bulbs?

6—“Henderson’s is a vital social message, and he seems more qualified than most to deliver it.”

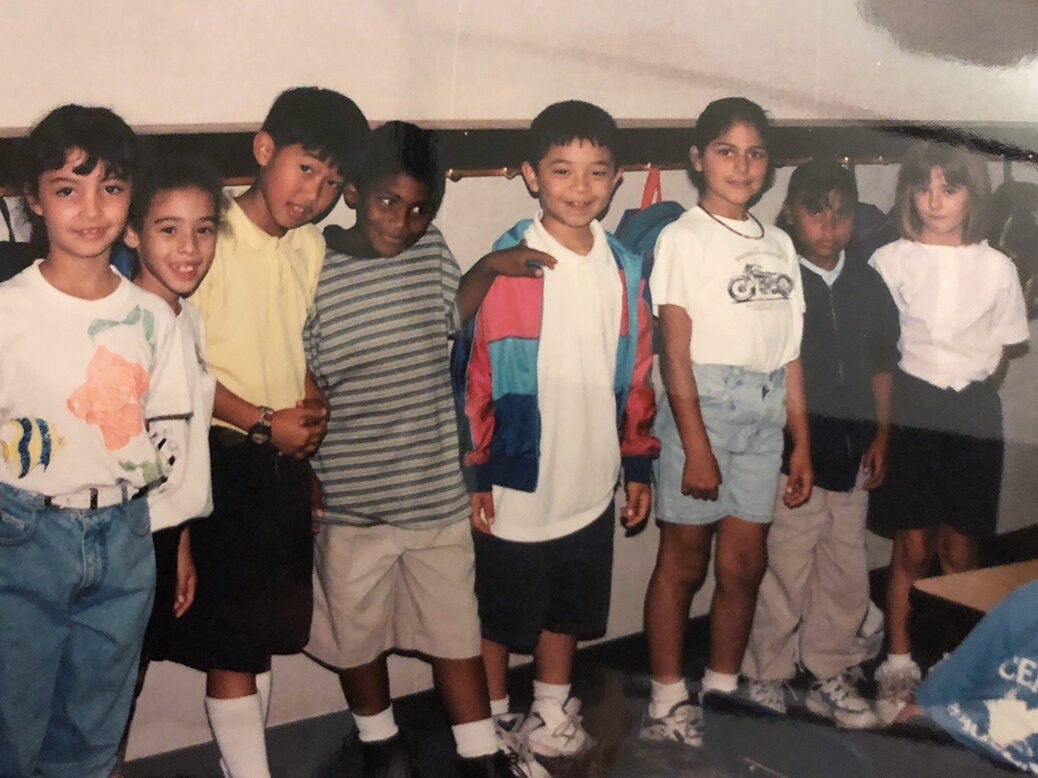

In January Rob Henderson described himself as an “unwelcome author” because no book shop would host an event for his new memoir, Troubled – perhaps because of his support for Jordan Peterson, or because his book was too polarising. For Troubled’s first 250 pages, which cover Henderson’s peripatetic and traumatic childhood in California, I struggled to understand why anyone would find it controversial. Then the book shifted gear. PB

The final chapters of Troubled build upon an article Henderson wrote in the New York Post in 2019 about what he calls “luxury beliefs”. Now that luxury commodities (“trendy clothes and other products”) are more easily available to the masses… the wealthy elite instead confer status upon themselves by espousing certain beliefs: monogamy is outdated; drugs should be legalised; defund the police. (Henderson doesn’t need to use the words “liberal”, “woke” and “virtue-signalling” for the political context to be clear.) Such views, Henderson argues, are easy for the upper classes to hold as they are not harmed by them.

7—“Britain is a nation beset by trauma.”

If leaders reflect their nation, does Keir Starmer’s ascendency mean Britain is a dull land? No, look closer, urges Will Lloyd. Starmer specialises in suffering. His grand vision is the “tabulation and redress of people’s pain”. That’s what we want now. But what will happen if he cheers us up? GM

Britain – and I don’t mean this pejoratively – is a nation of victims. The stories the country tells itself, whether they are real or fictional, are trauma plots. The agonising slow-motion televised decline and death of Kate Garraway’s husband Derek Draper, the former Labour insider, from Long Covid. The endlessly repeated story of Diana, Princess of Wales; since 2020, the subject of (at least) two plays, two series of television drama, two films, and an off-Broadway musical.

“Leave the poor Princess alone”, was the begging headline in the New York Times in January – but I doubt we will. She is too perfect a victim: shredded by a classic British institution; unable to speak any longer. Prince Harry speaks in her place. The language he uses to do so – ADD, PTSD, anxiety, depression – may have its origins in American psychiatric practice, but has gone on to colonise Britain.

8—“Taylor Swift has become a metaphor for the soul of America.”

Taylor Swift is a chameleon, her sound, aesthetic and politics shifting with every passing release. This shape-shifting gives the megastar a universal appeal that’s great for record sales, but as she has no coherent identity both left and right have projected their own anxieties and prejudices on to her. Finn McRedmond charts how Swift became a “blank slate for America to scribble its culture war lines on”. PB

Jonathan Haidt suggests that sometime between 2011 and 2015 a great split in the United States revealed itself. The campus-born, identity-obsessed left on one side, the Maga new right on the other. A decade on, there exists a Democrat party torn between the progressive extreme and the moderate centre; and the right, fully captured by the drain-the-swamp virtues of Trumpism. Taylor is tugged between these poles, not as her own person, but as a vector for America’s existential angst. It is easily done to an artist without a robust persona.

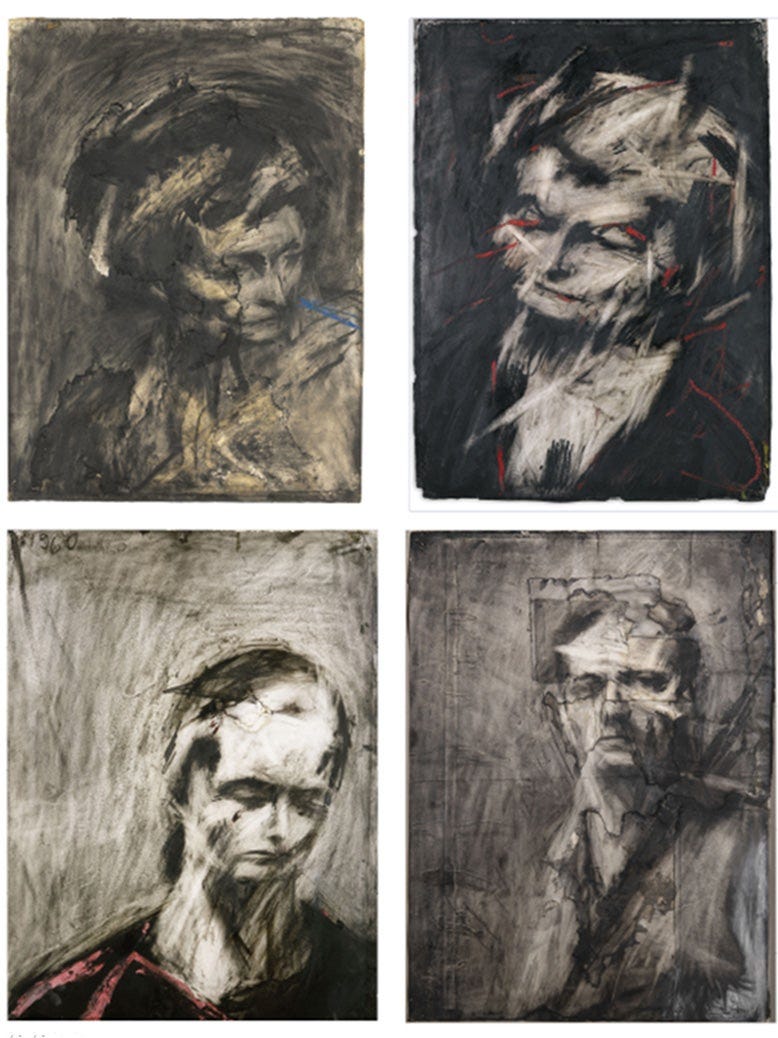

9—“The faces are made of light, not line.”

Michael Prodger reviews the charcoal faces of Frank Auberbach, now on show at the Courtauld. Auerbach, 92, is the last man alive of the Freud-Bacon “School of London” painters. (I love this graphite face of Auerbach’s; a veritable steal at $365,000 when it sold in November 2022.) HL

If Bomberg’s influence can be clearly felt there is another presence too: that of Käthe Kollwitz, a German artist of an earlier generation who used charcoal to similarly intense and unnerving ends. There is a haunted quality to her faces – the unshakeable weight of experience – that can also be felt in Auerbach’s. His sitters often look as if they have seen a ghost, the spectres perhaps of all those deleted images of themselves that went before.

Best of the Rest

Will is in Italy this week, so George has stepped in.

Guardian: Egypt sets up a “contingency area” for Rafah exodus.

BBC: Greece legalises same-sex marriage. Opa!

NYT: Why London’s skyline looks so weird. They’re just jealous we have the Cheesegrater.

WSJ: China’s shipyards are ready for war – America’s are not.

Paul Krugman: I’m bricking it in the US.

Tara Isabella Burton: On good parties. Study for Saturday night.

Alice Courtright: Do you need low self-esteem to dance?

Michael Wahid Hanna: Only the US can stop Rafah invasion.

Janan Ganesh: The rise of the political casual.

Watching television is a chore. Beyond first-world problems.

Romans on magic mushrooms. Why can’t a horse be, like, a senator, man?

The sickening truth about Guinness. That it’s £7 now?

Australian PM gets engaged, in office, on Valentine’s Day. Setting the bar high.

Milk and two sugars please. And grapefruit. Last time I invite this guy round.

Cultural corner: The return of Dodie Smith

Later in life, Dodie Smith would admit that she had always known her play Dear Octopus signalled the “end of an epoch”. It opened on 14 September 1938, and at the interval, word from the Times reviewer and novelist Charles Morgan spread throughout the theatre that Neville Chamberlain was expected to fly to Berchtesgaden the next morning, sending sighs of relief rippling through the audience.

The promise of peace offered by the subsequent Munich Agreement was short lived, and Smith would soon flee England with her husband, Alec Beesley, a conscientious objector, and effectively end her career as one of London’s most popular playwrights. Exiled in America, she would turn to novels and screenwriting instead, producing the books she is now best known for: the Disnified children’s story The Hundred and One Dalmatians and her coming-of-age classic I Capture the Castle.

Dear Octopus, written when she was in her early forties, was Smith’s sixth and last play performed in the 1930s. She described it as a story of “lamplight, candlelight, firelight, sunset deepening into twilight… a play of youth and age”. Eighty-six years later, it’s back on in London as part of a major National Theatre production, with Lindsay Duncan in the lead role.

The play takes place on the golden wedding anniversary of Charles and Dora Randolph, as their children, grandchildren and a great-grandchild gather at the ancestral home for a reunion of their large family, “that dear octopus from whose tentacles we never quite escape, nor, in our innermost hearts, ever quite wish to”. Dora, the matriarch of this unruly clan, is in a somewhat anxious “job-finding mood”, and her descendants are dispatched up and down stairs on various minor tasks as she worries about reuniting with her favourite daughter (“I never had any favourites. I loved them all equally. But I always liked Cynthia best”), who has been estranged from the family for seven years.

It’s hard to know quite what has inspired the revival. Smith’s plays were a hit in the 1930s, but she’s an unfashionable figure now. Last October, researching a piece on the enduring appeal of I Capture the Castle, I found myself in a library in Boston, surrounded by large boxes of Smith’s diaries, which she kept on painstakingly numbered sheets of loose-leaf paper. They are filled with anxiety, guilt and homesickness. The librarian couldn’t tell me when they had last been looked at.

Why now? Emily Burns’s production emphasises the pathos of Octopus’s late interwar setting, with radio broadcasts reporting on the latest crisis talks in Europe, but this is not a political play. Some of the comedy has dated (one joke, which revolves around the phrase “district nurse” being the rudest in the English language, doesn’t land as well today), and its happy ending bathes the play in a sentimentality – even a tweeness – that prevents it from feeling “modern”.

But there is humour and meaning here in universal human experiences, unchanged through the decades: the eternal dysfunction of the family unit, and the inescapable poignancy of one generation fading away as another roars into life. The family home circles on the spot like a dancer in a music box, as actors move from room to room, and gas lamps and roaring fires flicker against faded blue-green walls.

We now have a weekly ideas newsletter, The Salvo, written by Gavin Jacobson. Its fine second edition ran this Thursday. You can sign up here:

Elsewhere on the NS

Megan Nolan’s review of an expansive book about women’s relationship with porn is both compelling and horrific.

Nobody wants to see the morning routine of a depressed millennial, writes Kara Kennedy in this zippy take on the fading Soho House era. “What if I pack it all in and become an influencer, Soho House is the place to start, right?”

You know you want to read the former archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams on the boundary-breaking morality of Lord Byron.

Peter Gordon, the Harvard historian, wrestles with Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog.

Pippa likes Succession’s Sarah Snook and she wanted to like her one-woman production of The Picture of Dorian Gray, on in London until 11 May. But, unlike all the other rave reviewers, she did not.

Megan interviews Oren Cass, the rising star of Republican Party policy in the US, who has been described as a slaughterer of the party’s sacred cows.

There are worse qualities for a president than a poor memory, writes Jill Filipovic. Namely: instability, narcissism and sociopathy.

David Gauke makes a surprising bet: Priti Patel, opposition leader.

Duncan Weldon explains why the UK’s current recession isn’t actually mild at all.

It’s too late for Europe, but America can still prevent immigration from ruining its politics, Charlotte McDonald-Gibson writes. (It can?)

And with that…

“I’m Evgeny Lebedev,” says Baron Lebedev – of Hampton in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames and of Siberia in the Russian Federation – “and welcome to my podcast, Brave New World.” The good Lord says the podcast was inspired by his grandfather, an eccentric-sounding Soviet biologist. It is hosted by the Evening Standard, the somehow-still-existing newspaper Lebedev owns, among others, with his father, a peacefully retired KGB agent. Since Brave New World’s launch in January, it has failed to enter the top 250 on Apple’s UK podcast charts.

Forget the charts. With this venture Lebedev has at least managed something new: he is the first man to combine vanity publishing and vanity podcasting. Is it even a podcast? Lebedev has grander ambitions. “We live in a world in need of healing,” he says in his wintry Russinglish. Only 35-minute slabs of audio featuring “brilliant minds” can do the job. For the same effect, listen to Michael Jackson’s “Earth Song” seven times in a row – the same egotism dressed up as humanitarianism.

Hysterically, these “brilliant minds” are a load of guys who love shrooms. Oh, and Stephen Fry. The latest world-healing episode finds Leb in Costa Rica. He is there for “My Ayahuasca Journey”. What will this notoriously shit-stirring psychoactive brew dredge up from the insides of a KGB agent’s son with a reported net worth of $300m? Evgeny finds himself in an indigenous yurt with American drug tourists – tricky for a “solitary individual” (apart from when he’s holidaying with Boris Johnson) who “likes to be in control”.

Anyway, the potion! It is administered by shamans, and ingested. The experience is “humbling”, “healing”. His internal “hamster wheel” stops. The “ancestral trauma” of Stalin’s purges materialises before him in a vision. Listening to all this druggy chat is Dr David Nutt. He burbles scientifically as Lebedev drones on. One can hear such conversations – looping, implausible, narcissistic – in apartments across east London on any night of the week. Brave New World is what happens when they become a podcast.

If today’s pieces intrigued, why not subscribe to the New Statesman? Stay up to date with everything you need: from news and analysis to comment, criticism and essays.

Whether you’re looking for a sharp blog or a finely written feature, the New Statesman has you covered. Have a good week, and catch you next Saturday.

Trump will come and go, but climate change will only come; it won't go away during the lifetime of anyone who is alive now.

"Collapsing birthrates" are actually needed for a sustainable planet.